I. INTRODUCTION 1

II. MAYOR'S WORK GROUP AND DELIBERATIVE PROCESS 2

A. Appointment of Work Group and Mayor's Charge 2

B. Composition of Work Group 3

C. Deliberative Process 4

III. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 5

IV. RECOMMENDATIONS 8

V. PIIAC-HISTORY, OPERATIONS, STRENGTHS AND WEAKNESSES 11

A. History of PIIAC 11

B. Operations and Process 13

C. Current Police Oversight System Strengths and Weaknesses 15

VI. RESEARCH AND OTHER OVERSIGHT MODELS REVIEWED 20

A. Overview: Explanation of Audit vs. Independent Models 20

B. Models of Other Review Boards Examined 21

1. Minneapolis Civilian Police Review Authority (CRA) 23

2. Pittsburgh Citizen Police Review Board (CPRB) 24

3. County of San Diego Citizensí Law Enforcement Review Board (CLERB) 25

4. San Francisco Office of Citizen Complaints (OCC) 26

5. Honolulu Police Commission (HPC) 26

6. San Jose Independent Police Auditor (IPA) 27

C. Expert Consultations 28

Flow Charts 29a/b

VII. PROPOSED CHANGES TO PIIAC 30

A. Introduction 30

B. Review Board Scope of Authority 30

1. Independent investigations 30

2. Optional Police Investigation 35

3. Compelling civilian and officer testimony 36

4. Binding authority on finding of misconduct 40

5. Recommendation to impose discipline 41

6. Public Hearings and Policy Recommendations 43

7. Shootings/deaths in custody 45

8. Appeals 48

9. Early Warning System 48

C. Structure and Staffing 50

1. Selection and training of Members 50

2. Number of investigators 51

3. Timeliness 52

4. Location of the board 53

5. Outreach 54

6. Process evaluation forms 55

D. Intake of Complaints 56

1. Dual intake--IAD retained 56

2. Sworn vs. unsworn complaints 57

3. Community intake sites, volunteer advocates, and training 59

E. Mediation 60

VIII. CONCLUSION 62

IX. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 63

X. GLOSSARY TO TERMINOLOGY USED 64

Appendices A - U

Back to top

This report embodies the recommendations, discussion and analysis of the work group appointed by Mayor Katz to review the Police Internal Investigations Auditing Committee (PIIAC). The report represents and explains in particular the recommendations made by a majority of the 18 members of the work group.1 2The reportís recommendations are based upon the research, discussion and analysis of the work group spanning over a period of several months. The report also incorporates the unanimous recommendations of the work group. In addition to this report, a minority report has been written reflecting the views of other members of the work group. Wherever possible, this report addresses the concerns and positions of those members. See the end of this report for Glossary to terminology.

Back to top

II. MAYOR'S WORK GROUP AND DELIBERATIVE PROCESS.

A. Appointment of Work Group and Mayor's Charge

In May, 2000, Mayor Vera Katz appointed a volunteer work group. The Mayor issued the following statement with directions for the group:

Background

Mayor Vera Katz began the process of re-evaluating the Police Internal Investigations Auditing Committee (PIIAC), as she had previously done in 1993. This task was begun by Lisa Botsko, the previous PIIAC Examiner, and has now been assigned to Michael Hess, the current PIIAC Examiner.

Various community groups and individuals have voiced concerns about the citizen review process in Portland. The Police Accountability Campaign 2000 has started an initiative process. The Portland Chapters of the NAACP and the National Lawyers Guild (NLG) have joined with other concerned individuals and groups to propose changes through the Mayor and City Council. On May 1, the leaders of the NAACP/NLG group presented their proposals to Mayor Katz at the City Hall. Mayor Katz received their proposal document and assured them that she would review the proposed changes.

Mayor Katz has decided to form an ad hoc work group to examine Portlandís citizen review process and to propose recommendations that she can take to the City Council. This PIIAC-sponsored work group will optimally consist of representatives of the NAACP/NLG group, PAC-2000, current PIIAC Citizen Advisors, Copwatch, the Police Bureau, the Portland Police Association, the Citizens Crime Commission, the Metropolitan Human Rights Center, a former PIIAC Appellant, former PIIAC Advisors, leaders of minority and under-represented communities, a representative of the City Attorneyís Office, and the PIIAC Examiner.

Charge of the Work Group

1. To examine the strengths and weaknesses of the current PIIAC process.

a. What is working well?

b. What needs to be improved?

2.To research "best practices" in citizen review processes of other cities.

a. To obtain policies and data from other U.S. cities.

b. To study and compare various models of citizen review.

3. To host public meetings to gather community input on improvement options.

4. To evaluate and recommend improvements to PIIAC.

B. Composition of Work Group

The entire work group was composed of the following members:

|

NAME |

AFFILIATION |

|

Charles Ford Ric Alexander |

Current PIIAC chair PIIAC Citizen Advisor (Alternate for Charles Ford) |

|

Denise Stone |

Current PIIAC vice chair |

|

Robert Wells |

PIIAC Citizen Advisor |

|

Alan Graf Mark Kramer |

NAACP/National Lawyers Guild National Lawyers Guild (Alternate for Alan Graf) |

|

Bruce Broussard |

NAACP |

|

Diane Lane |

NAACP Researcher |

|

JoAnn Bowman |

African American Police Advisory Council |

|

Dan Handelman |

Portland Copwatch |

|

Ray Mathis Tom Johnston |

Citizens Crime Commission Citizens Crime Commission (Alternate for Ray Mathis) |

|

Amalia Alarcon-Gaddie |

Metropolitan Human Rights Center |

|

Will Aitchison Greg Pluchos |

Portland Police Association Portland Police Association (Alternate for Will Aitchison) |

|

James Simpson |

Former PIIAC Citizen Advisor |

|

Todd Olson |

Former PIIAC Chair |

|

Darleane Lemley Barbara Clark Debbie Aiona |

League of Women Voters League of Women Voters (Alternate for Darleane Lemley) League of Women Voters (Alternate for Darleane Lemley) |

|

Preston Wong |

Asian American Representative |

|

Lorena (Nena) Williams |

PIIAC Appellant |

|

Guy Crawford Bryan Pollard |

Transition Projects Street Roots (Alternate for Guy Crawford) |

|

TJ Browning |

Mayor Katz's Appointee |

In addition, former PIIAC Examiner Lisa Botsko, was initially appointed to the work group but withdrew six weeks into the process. Lori Buckwalter, a member of Sexual Minorities Roundtable and also an initial appointee resigned about eight weeks into the process.

C. Deliberative Process

The work group met 14 times, beginning on May 30, 2000 and concluded with a meeting on September 12. The July 11 session was dedicated to hearing public testimony. The work group will meet on October 30, 2000 to adopt its final reports.

The process was guided by Dr. Michael Hess, current PIIAC examiner. Several of the meetings were facilitated by Ms. Cherise Millhouse, of the Office of Neighborhood Mediation, while others were facilitated by members Charles Ford and T.J. Browning. Several experts were specially invited and participated in the meeting process, including Deputy City Attorney David Lesh, Portland Police Bureau (PPB) Chief Mark Kroeker, and police oversight experts Dr. Samuel Walker and Mark Gissiner.

During various meetings, straw votes on key decisions and recommendations were taken. On September 12, final votes were taken on all recommendations. A description of the votes taken on the 28 motions and record of the vote of each work group are set forth in Appendix A.

Dr. Hess and others took notes of each meeting session and many, but not all of the meetings were audiotaped and/or videotaped. There is no official written record of the work groupís deliberations.

The work group had no staff or budget. In addition to the components that are addressed in this report, the following components of civilian review were mentioned during discussions but never formulated and voted upon: Removal of board members; right to representation/volunteer advocates; information shared with complainant; public input; role of City Council-Mayor-Police Commissioner-Risk Management-City Attorney; and standard of proof utilized in the final assessment of the merits of a complaint.

Back to top

III. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY.

After a lengthy examination of Portland's police oversight system and other models of police oversight from across the country, the work group concludes and recommends to the Mayor that the current Police Internal Investigations Auditing Committee (PIIAC) be substantially expanded by giving it additional powers including, but not limited to, the authority to conduct independent investigations, compel testimony, make final findings as to the merits of a complaint and review investigations of police shootings and deaths in custody.

Notwithstanding several well-intentioned efforts to strengthen and reform PIIAC since its establishment in 1982, PIIACís institutional limitations still critically limit its effectiveness. For example, PIIAC can currently only audit but cannot independently investigate allegations of police misconduct. It has limited staff and resources. Because PIIAC can only begin its audit review after completion of an Internal Affairs Division (IAD) investigation, the entire process to resolve a citizenís complaint is unacceptably long. Ongoing deficiencies in Police Bureau investigations and unsupported findings of "exonerated" suggest a lack of impartiality in the examination of citizen complaints. Further, many citizens feel intimidated by a citizen complaint system in which police officers investigate other police.

PIIACís decisions are not binding and in two fairly recent cases, findings were rejected by the Chief of the Portland Police Bureau (PPB). PIIACís ability to review police policies and make effective and meaningful recommendations is extremely limited.

As a result of these chronic shortcomings, PIIAC and IAD, have never established credibility with Portlandís citizens, particularly those in the minority, homeless and indigent communities. Many citizens, especially those from such communities are reluctant to file complaints of police misconduct with the police because of fear of retaliation and the belief that the complaints will not be treated seriously.

Thus, PIIACís shortcomings are institutional in nature. Major reforms are necessary to ensure that allegations of police misconduct are fairly, credibly, impartially and effectively investigated and assessed. To perform its job within these expectations, the reformed PIIAC:

- Must be able to conduct independent investigations of allegations of police misconduct;

- Must be given the power to compel civilian and police officer testimony and evidence;

- Must be able to make a binding decision on whether or not police misconduct occurred;

- Must hold public hearings on PPB policies and procedures, make recommendations, and have those recommendations implemented or addressed by the Chief and the Police Commissioner if not implemented;

- Must be able to review completed investigations of police shootings and deaths in custody, and make its findings public;

- Must allow civilian intake of complaints at sites other than the Police Bureau or City Hall;

- Must be given adequate civilian staff and resources;

- Must have thoroughly trained members; and

- Must have the power to recommend whether discipline should be imposed on an officer, leaving the type of discipline imposed in the hands of the Police Chief.

Some work group members agree on certain recommendations because they can be implemented regardless of whether PIIAC remains an auditing board or becomes an investigatory board. However, the majority of the work group urges the Mayor to implement all of our recommendations which we believe would result in transforming the current PIIAC into a civilian system of police oversight that would better promote credibility, citizen trust and accountability in Portland.

Respectfully Submitted,

Denise Stone, Current PIIAC Vice Chair

Alan Graf, National Lawyers Guild

Mark Kramer, National Lawyers Guild

Bruce Broussard, NAACP

Diane Lane, NAACP

Jo Ann Bowman, African American Police Advisory Council

Dan Handelman, Portland Copwatch

Amalia Alarcon-Gaddie, Metropolitan Human Rights Center

Todd Olson, Former PIIAC Chair

Darlene Lemley, League of Women Voters (former Member of Storrs Commission)

Barbara Clark, League of Women Voters

Debbie Aiona, League of Women Voters

Lorena (Nena) Williams, PIIAC Appellant

Guy Crawford, Transition Projects

Bryan Pollard, Street Roots

T.J. Browning, Mayor Katz's Appointee

Back to topIV. RECOMMENDATIONS- The Following is the Actual Language of the Recommendations Passed by a Majority and/or Unanimous Vote of the Work Group.3

#1. That, regardless of which model is recommended, there be a feedback instrument for both the complainant and the officer and that the feedback be optional and that statistics be kept.

#2. That a dual intake procedure be initiated, making it possible for persons who are afraid or reluctant to go to the police with their complaints to go to another office outside the Police Bureau, where the complaints will be taken by non-police personnel.

#3. That the civilian review system have the ability to perform independent investigations of allegations of police misconduct.

#4. That there not be dual investigations of citizen complaints, and that citizens have the ability to choose either IAD or the civilian review board to do the investigation, but not both.

#5. That the Police Chief and the Police Commissioner be required to respond in writing to policy recommendations within sixty days; and that if the review board is not satisfied with the Chief's/Commissioner's response, he/she must publicly present his/her response to the City Council.

#7. That PIIAC/the review board have the power to review completed investigations of police shootings and deaths in custody, regardless of who conducts the investigation, and that the board's findings be made public.

#9. That sworn statements not be required at the intake stage.

#10. That an oath (sworn statement) be required if a case is deemed worthy of investigation, especially if the statement is to be given evidentiary weight.

#11. That investigations into alleged police misconduct should be completed within 70 days as per the current General Order.

#13. (a) That PIIAC (if it remains an Auditing Body) be able to change a Police Bureau finding and that this disposition be binding; (b) that the citizen review board have the authority to make a final finding that is binding.

#15. That the final say on discipline belongs to the Chief of Police.

#16a. That the citizen review board have the ability to recommend that discipline happens, and that the Chief/Commissioner should respond in writing within thirty days with an explanation if the recommendation is not accepted.

#17. That PIIAC's recommendation that there be one investigator per 100 sworn officers be forwarded to City Council.

#18. That regardless of the model chosen, hearings will be public with the exception of personnel, medical, employment, and criminal issues and at the discretion of the committee.

#19. That the model will allow for public hearings to discuss police policy and recommend changes to the police chief/commissioner.

#20. That the board be granted power to compel testimony of witnesses, including police officers, subject to due process and right to counsel, and that the City Council should implement changes to the City Charter or recommend changes to state law as necessary to effect this power.

#21. That the review board/PIIAC be located in a building separate from City Hall and the Police Bureau.

#22. That members be appointed rather than elected and that term limits be instituted.

#23. That complete training be mandated for all citizen members, to be completed within a specific period of time following appointment.

#24. That complaint forms and training be made available to all social service agencies, community centers, and neighborhood associations.

#25. That training be made available to volunteers to help complainants file complaints and move through the process.

#26. That the City hire necessary staff/resources to coordinate the process for implementing the previous two recommendations and that those resources be available to provide training.

#27. That the necessary resources be designated to design and implement a Public Awareness Outreach Program.

#27a. That regardless of the model, mediation should be available to all parties involved.

Back to top

V. PIIAC-HISTORY, OPERATIONS, STRENGTHS AND WEAKNESSES.

In 1981, Portland City Commissioner Charles Jordan, in charge of the Police Bureau, appointed a citizen task force, known as the Storrs Commission, to review the citizen police complaint process. After a six-month investigation into the Internal Affairs Division (IAD), the Storrs Commission issued its report and concluded: "Many citizens have no confidence in the IAD and its procedures and are therefore reluctant to file complaints with the police." 4 The Storrs Commission recommended the establishment of a permanent citizensí advisory committee to hear citizen appeals of IAD findings. The recommendation, after several modifications, was approved by the City Council on a 3-to-2 vote on April 8, 1982. 5

The president of the Portland Police Association (PPA) led a successful petition drive, organized and financed by the PPA, to put the matter before the voters with the intent of having the voters disapprove of the new advisory committee. Nonetheless, the voters approved the measure by an extremely narrow margin.

The Police Internal Investigations Auditing Committee (PIIAC) was established as a subcommittee of City Council, with a number of Citizen Advisors performing most of the actual work. Since its establishment, PIIACís primary role has been to monitor the internal investigations process and to hear appeals of police investigations.

In the late 1980's, a number of advisors attempted to use the subpoena power granted to the Council as PIIAC in a investigatory manner. They were advised that because PIIACís authority is limited to that of an auditing committee they could only use the subpoena power to ask questions about the internal investigations process. Several advisors resigned in frustration.

In 1989, the City Council revised the City Code to define PIIAC as the five members of the Council, among other non-substantial changes.

In January 1993, the City Auditor issued a report on PIIAC entitled, "Portlandís System for Handling Citizen Complaints about Police Misconduct Can Be Improved." Appendix B.

The Auditor concluded:

PIIAC has not accomplished its objectives. Although cases appealed from IID are reviewed thoroughly, PIIAC has failed to adequately monitor, review and report on the police internal investigation system as required by City Code. As a result, PIIAC provides insufficient assurance that the IID process is fair and accountable. Many of the citizens we interviewed were critical of PIIACís accomplishments.

The Auditor found that investigations in 1991 required an average of 137 days to complete. The most recent 1999 statistics indicate that the average process takes about 13 months to complete (about 390 days). 6

As a result of the Auditorís report and community input, in November 1993 Mayor Katz added the option of mediation to the system of police oversight. The mediation process is voluntary for both the complainant and the police officer.

In January 1994, the "Mayor's Initiative" added a number of additional changes to the system including: adding two more advisors (from 11 to 13); relegating the power of appointment of seven of the advisor positions to neighborhood coalition offices; providing IAD forms and intake training to coalition offices and other locations; placing a PIIAC representative on the Chief's Forum; and creating a community outreach program. The Mayorís Initiative also established a full-time staff person for PIIAC; moved the staff out of the Auditor's office to the Commissioner in charge of PIIAC; and allowed PIIAC to sit in on the "Review Level Committee" meetings of the Police Bureau in cases where advisors found the findings were not justified by the evidence presented.

Elements of the "Mayor's Initiative" which have still not been implemented include provisions for soliciting community feedback about police policy issues (Community Outreach Program) and the use of the statistics of the Office of Risk Management for PIIAC monitoring reports. The Chief's Forum has never reviewed information presented to it by PIIAC.

In 1997, the Police Chief rejected PIIACís recommended findings in two appealed cases.

In February 1998, the City Council held an informal session to address their questions concerning the Police Chiefís ability to ignore the Councilís final recommendations. While there was some discussion about ways to change PIIAC's structure, the end result of the informal session was a suggestion by the Council to create a citizen's group to review PIIAC.

In the spring of 2000, the Police Accountability Campaign (PAC-2000), an ad hoc citizens group, filed a ballot measure to give PIIAC the powers of a civilian review board including the hiring of independent investigators and the ability to mandate changes in police policies. The sponsors of the measure gathered 20,000 of the necessary 20,950 signatures narrowly missing qualification for placement on the ballot.

In May 2000, the Portland chapter of the NAACP and the Portland chapter of the National Lawyers Guild (NLG) jointly presented the Mayor and the City Council with a proposal for "a reform of the current citizen police review board (PIIAC)." The proposal was signed by community leaders, community groups and leaders of the faith community. Shortly thereafter, Mayor Katz appointed this work group to study the issues.

B. Operations and Process.

PIIAC is comprised of the City Council and thirteen citizen advisors. PIIAC currently has one paid staff person. The complete city code which establishes PIIAC is attached as Appendix C.

A citizen may not complain directly to PIIAC. They must first pursue a complaint through IAD. After an investigation conducted by IAD, the appropriate supervisor in the PPB issues a finding regarding whether the officer committed an act of misconduct based on the investigation.

A citizen also has the option to pursue mediation as an alternative to a full IAD investigation. However, if mediation is not successful, there will be no IAD investigation and therefore no appeal to PIIAC. A citizen or a police officer dissatisfied with the results of an IAD investigation can file an appeal with PIIAC within 30 days of the mailing of the IADís notice to the complainant (or officer) of its findings.

At the conclusion of the PIIAC review, Citizen Advisors may affirm the Bureau's findings, recommend that IAD take the case back for further investigation, refer the matter to the Bureau's Review Level Committee for further investigation, or recommend that the finding be changed because the facts did not support the Bureau's decision.

PIIAC may require the Commander of IAD to appear and answer questions regarding the investigation in the normal course of its work. The Portland Code provides that, in "extraordinary circumstances" PIIAC may compel City employees or citizens to appear and testify by issuing a subpoena. This power has never been used.

In addition to hearing appeals of IAD investigations, PIIAC must prepare quarterly reports highlighting trends in police performance and state the Citizen Advisorsí findings, conclusions and recommendations regarding changes in police policy and procedures. Patterns of behavior, unclear procedures and policy issues, and training needs may be identified for review. The basis for these recommendations are the appealed cases and randomly audited closed files at Internal Affairs.

The PPB Chief, after reviewing a PIIAC report, must respond to PIIAC in writing within 60 days regarding what, if any, changes are to be made. If the Chief fails to respond, the matter is placed on the City Council calendar.

PIIAC is not involved in all cases of alleged police misconduct. Cases involving aggrieved citizens who pursue litigation, who pursue mediation as an alternative to a formal IAD investigation, or who do not challenge the results of the IAD investigation are not necessarily reviewed by PIIAC.

C. Current Police Oversight System Strengths and Weaknesses.

At its first meeting, the work group brainstormed about strengths and weaknesses of the current Portland police oversight system. We realized that a complete examination of PIIAC's process needed to include an assessment of IAD's citizen complaint system including investigation. The following chart was constructed:

|

Strengths |

Weaknesses |

|

public knows about PIIAC |

lack of independence and lack of due process |

|

mere existence of PIIAC is a strength (basis to build on) |

lengthiness leads to expensive lawsuits |

|

interest in improvement (advisors) |

no teeth/independence |

|

outreach to community |

lack of community trust |

|

public announcements |

lack of training [for advisors] |

|

information to appellants prior to hearing |

erroneous wording in City Code overlooked |

|

diversity of advisors best itís ever been |

citizens unable to take complaints directly to PIIAC |

|

monitoring trends and recommendations |

language problem (lack of bilingual/multilingual staff in IAD/PIIAC) |

|

mediation offered to citizens by IAD |

mediation not used enough |

|

provides citizens a window into IAD |

police not permitted to request mediation--only citizens |

|

full time staff person |

PIIAC Examiner asked to perform non-PIIAC duties |

|

|

public input at end of meetings instead of prior to votes |

|

|

Citizen Advisors' lack of knowledge of Police General Orders and constitutional values |

|

|

lack of sworn testimony by complainants |

|

|

citizens afraid to go to police (especially African-Americans) |

|

|

only audit--no independent investigation |

|

|

PIIAC makes recommendation only--can be rejected by Chief |

|

|

too many layers in PIIAC (convoluted structure) |

|

|

most policy recommendations are centered on IAD |

|

|

lack of accused police officers at PIIAC meetings |

|

|

PIIAC not able to examine police shootings/deaths in custody |

|

|

excessive length of time for IAD investigations |

|

|

lack of citizen academy to understand the appellantsí point of view |

|

lack of consistency in IAD |

|

|

|

Chiefís Forum does not pay attention to monitoring reports 7 |

In particular the work group noted that one strength of PIIAC is its statutory mandate to produce monitoring reports. These monitoring reports helped the work group identify problems in the Internal Affairs process and identify policy issues which needed addressing. A number of the problems identified by these reports were used by the work group in its analysis and subsequent recommendations.

For example, from a study of the PIIAC monitoring reports, the work group determined that IAD investigations of citizen complaints were deficient with some regularity. The 2nd/3rd Quarter 1998 monitoring report based upon the tapes of IAD interviews with police officers listed the following problems which were conducted as part of the citizen complaint investigation:

Asking leading questions

Giving too much time to officers during interviews

Not pursuing relevant witnesses

Not enough preparation by investigators 8

This same Advisors' report described a chronic lack of timeliness in police investigations and noted some unsupported findings of "exonerated" (officer acted within bureau policy). Although PIIAC made recommendations to IAD to implement investigative improvements consistent with the deficiencies noted, there is no evidence that these improvements were made. The deficiencies noted in the PIIAC monitoring reports primarily occurred in citizen complaint investigations, but not in internally generated complaint investigations. This raised the possibility of disparate treatment by IAD of citizen complaints in contrast to fellow officersís grievances.

The work group also considered evidence from a number of sources that the current PIIAC process is not perceived to be credible by sections of the community, especially the minority community. This evidence was derived in part from accountings of anecdotal stories from members of the work group who represented minority and the homeless communities. Consistent with this evidence, the conclusion of the 1992 City Club report continues to be relevant notwithstanding the reforms made after the report was issued:

The limitations on PIIAC's role minimizes its influence on police conduct and effectiveness on behalf of the citizens with complaints especially those from racial and ethnic minority groups. PIIAC has virtually no power. Moreover, the processes for bringing complaints to the Portland Police and for requesting PIIAC review assume that complainants can communicate effectively in English, understand the American law enforcement system, and believe in the impartiality of law and the integrity of the judicial process. The fact that few members of racial or ethnic minority groups bring complaints to the PIIAC suggests that the present monitoring process is not inclusive of their needs. There is no actual citizen appeal process that allows independent investigation and recommendation. There is no systematic means at present to assure police accountability. 9

The 1992 City Club report recommended that: "The current PIIAC should be dissolved" in favor of " . . . a citizen oversight agency or process that better meets those needs of the entire community." 10

When PIIAC reviews investigations of citizen complaint appeals it periodically sends a case back to IAD when it finds that the investigation is lacking. On cases that are randomly monitored by PIIAC which are not appeals, investigative deficiencies can only be noted and not addressed. In other words, PIIAC cannot send such cases back for more investigation. In 1997 and 1998, out of the 30 appeals accepted and reviewed by PIIAC, 9 cases (30 percent) were sent back to IAD for further investigation. In the same time period, PIIAC monitored an additional 143 cases, leaving 201 closed IAD cases untouched by PIIAC in that time period.

The above concerns expressed by the work group regarding the weaknesses in the PIIAC audit model were echoed by the vast majority of citizens who attended the public session convened by the work group on July 11, 2000. The majority of the 50 to 60 people who attended the session called for the creation of an independent civilian review board separate from the police department. Most attendees claimed that they felt intimidated by the process of having to file a complaint with the police about police misconduct. Those same people expressed the opinion that PIIAC was ineffective. One person from the PAC-2000 Campaign presented a large stack of petitions with over 20,000 citizen signatures that were gathered in favor of the creation of an independent citizen police review board. Only two people of the group favored an audit style model of review, but they also favored substantial changes to the current system.

The work group also took note of other publicly expressed concerns about PIIAC, including those addressed by The Oregonian ("Improve Policing Of Police: Portland's system of civilian oversight needs change," editorial, June 9, 2000)(Appendix Q), The Skanner ("Police Bureau Needs Accountability", editorial, November 4, 1998)(Appendix R), and the NAACP and the NLG in their joint proposal. Appendix E.

Finally, the work group discovered that Professor Ken Adams of Indiana University, Perdue University at Indianapolis was in the process of conducting a survey of six cities' police complaint processes. This study is being funded by the National Institute of Justice. Although Professor Adamsí report has not been released to the work group, he related to one of the work group members via telephone that his study indicated a high level of citizen dissatisfaction with Portland's citizen complaint system. 11

The above weaknesses noted within the PIIAC audit model and this work groupís recommendations are not new. A similar analysis and proposal was suggested to the City back in June 1993 by the group "People Overseeing Police Study Group" (POPSG), the predecessor to Portland Copwatch.

In sum, taking into account the history of PIIAC, prior research conducted, prior recommendations, anecdotal evidence from communities at large, and the various reforms which have been instituted but have shown to be ineffective, the work group concludes that the weaknesses of the current PIIAC audit system substantially outweigh its strengths.

VI. RESEARCH AND OTHER OVERSIGHT MODELS REVIEWED.

A. Overview; Explanation of Audit vs. Independent Models.

Having identified significant problems with PIIAC and the audit model, the work group examined citizen police review systems across the United States. Diane Lane, NAACP researcher and work group member, prepared a research notebook for the work group which included data from review boards in Minneapolis, San Francisco, San Jose, and Pittsburgh, as well as a documented report on independent investigation, a policy recommendation comparison and a report on subpoena power. Ms. Lane also provided the work group with information obtained primarily from phone interviews she conducted with directors and staff at other citizen police review boards, as well as police oversight experts. Data on the Honolulu Police Commission, Seattle Police Oversight Task Force and Austin City Council Police Oversight Focus Group were provided by Robert Wells. Copies of the data and documents were provided for the work group by group member Todd Olson.

The sum and substance of this research data indicated that citizen police oversight is a relatively new entity in the U.S. with many review boards having a life span of less than 10 years. Within this country, there are approximately 100 oversight systems in place, but that number is growing rapidly since many cities are in the process of creating citizen police oversight systems. Although Professor Walker, a police oversight expert told the group that there are basically four models of police oversight with many variations of the four types, essentially three out of the four are modifications of the audit model. Since PIIAC is a hybrid audit system, our research primarily focused on independent review boards.

The two primary models are defined below:

Auditing Model: In an auditing model, trained staff and/or civilians review police investigations of citizen complaints, examining such investigations for impartiality and thoroughness. The auditors cannot change the police findings but can usually recommend either that a finding be changed, or that the investigation needs further work. In some audit models, the auditors make policy recommendations to the police chief or city manager. Most audit boards review only a certain percentage of closed police citizen complaint investigations. Some audit boards like PIIAC also provide an appeals process for complainants who disagree with the police departments' findings.

Independent Review Board Model: The composition of an independent review board usually includes volunteer non-police board members who are appointed after an application process through the Mayor and City Council. The board members hire a non-police staff--a director, investigators and support staff. The non-police personnel investigate citizen complaints. Findings are made by the directors and/or board members who hold either public and/or private hearings. Some independent boards make discipline and policy recommendations to the police chief or city manager. Independent boards have the power to compel officer cooperation during investigations, usually through specific language in the city charter and/or police general orders which mandate cooperation. Some boards have the power to conduct parallel investigations and/or review police investigations of police shootings and deaths in custody. Some boards implement the Early Warning System, which identifies potential problem officers.

B. Models of Other Review Boards Examined.

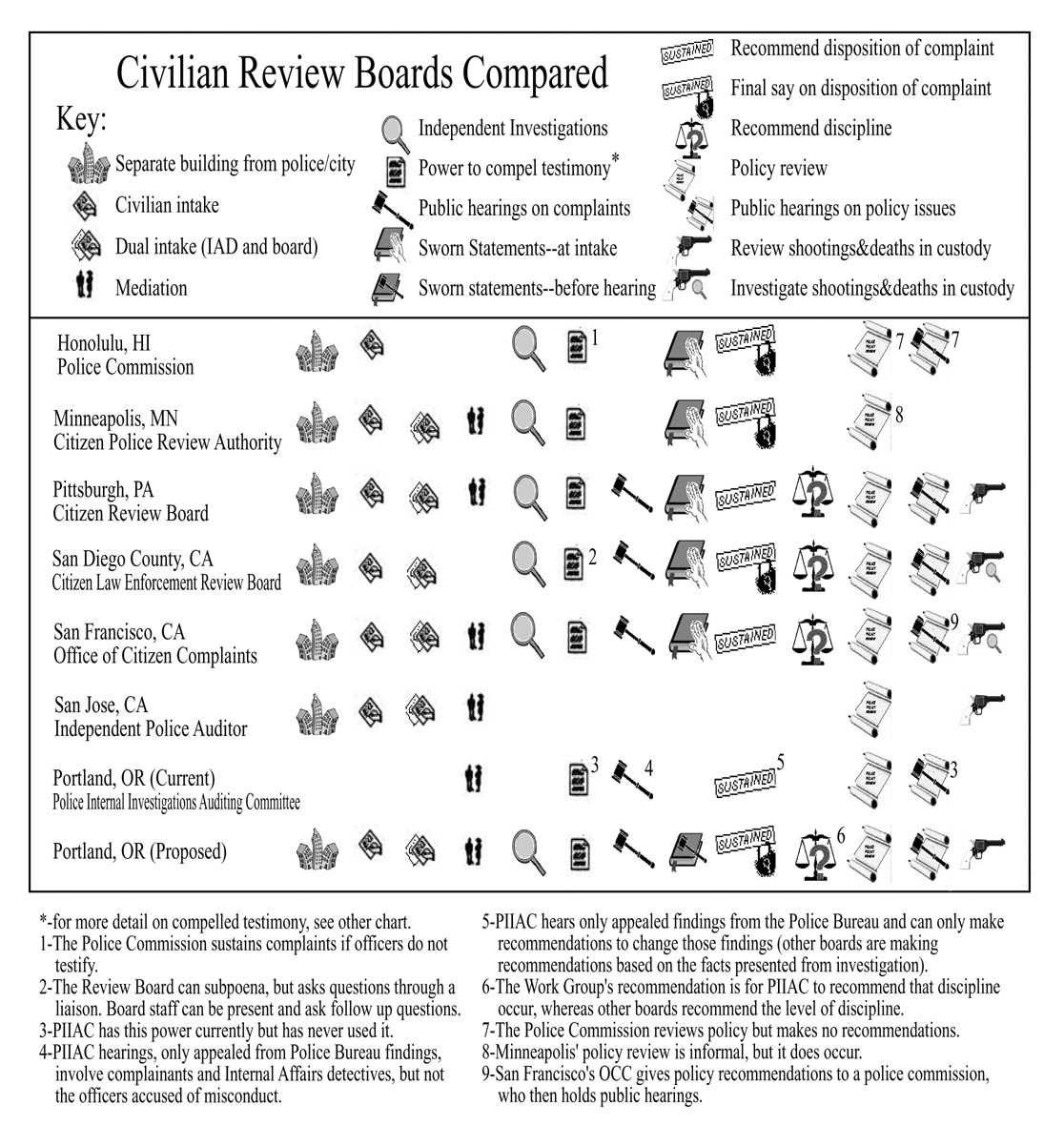

The work group examined the review boards in six other cities: Honolulu, Minneapolis, Pittsburgh, San Diego County, San Francisco and San Jose. A chart summarizing and comparing the elements of those boards is provided below.

With the exception of the San Jose model, all of the other review boards have independent investigatory power. The San Jose board relies upon an independent police auditor who can attend the internal affairs interview and suggest questions to the interviewer. All of the other boards except for San Jose have the power to compel testimony. (See this reportís discussion below regarding compelling witness testimony.) Similarly, some of the boards studied have final say as to the merits of a complaint. The boards of Pittsburgh, San Diego and San Francisco can make recommendations as to type of discipline merited.

The following is a more detailed description of each of the review boards examined.

1. Minneapolis Citizen Police Review Authority (CRA).

The Citizen Police Review Authority (CRA) was voted into existence in 1990. There are seven board members, one director, three civilian investigators and three support staff. All members and staff receive training in police procedures. The CRA handles over 800 complaints a year.

Complaints are assigned to an investigator who performs a preliminary review on all signed complaints. Based on the outcome of such a review, the director decides whether the case is dismissed or set up for full investigation. Many less serious cases are referred to mediation. The City Charter and the board's Administrative Rules mandate officer cooperation during investigations. Under such language, the Chief of Police is required to order the subject officer to cooperate and issues the Garrity Warning. 12 After investigation, a complaint sustained by the director will be heard by a number of board members in a private hearing. Several layers of review for the investigations as well as appeal opportunities for the complainant are set up throughout the complaint process. The board makes a final determination as to the merits of the allegations. The Chief of Police makes a disciplinary decision. The board makes informal policy recommendations and is active in community outreach.

(Population - approx. 350,000, # of police - 940, Budget - $500,000)

Professor Sam Walker analyzed the 1999 the CRA evaluation forms in which over fifty percent of the citizens as well as over 85 percent of the officers involved in the citizen complaint process found the board to be impartial and fair. He noted that this evaluation demonstrated that the CRA had achieved fairness and impartiality in the investigation of citizen complaints about police misconduct.

Professor Walker noted that both citizens and police officers who had contact with the Minneapolis board gave the agency extremely favorable evaluations: 71% of the citizens and 91% of the police officers felt that the Minneapolis board treated them with respect. 76% percent of the citizens and 90% of the police officers reported that in their contact with the Minneapolis board, they had a chance to tell their side of the story. Professor Walker concluded that, "compared with evaluations of other citizen complaint procedures, the ratings given the Minneapolis [board] are extremely high." 13

2. Pittsburgh Citizen Police Review Board (CPRB).

The CPRB was created by voter approval in 1997 after the U.S. Justice Department charged that there was a "pattern or practice" of conduct by officers of the Pittsburgh Bureau of Police which deprived citizens of their constitutional rights and protections. The CPRB includes seven volunteer board members who hire one director, seven staff persons and civilian investigators, and one attorney. Members are appointed by the Mayor and/or City Council and are extensively trained in police procedures, police training methods, and civil, constitutional and human rights.

After the CPRB receives a sworn complaint (it can also take anonymous complaints), a preliminary inquiry is performed. If the complaint is deemed viable at this point, and the complainant or officer refuse mediation (if applicable), there is a full investigation. If the complaint remains viable, and the CPRB believes it appropriate, a public hearing is ordered. The board makes specific discipline recommendations on sustained complaints.

The CPRB also makes policy, training and hiring recommendations. Its Rules and Operating Procedures include language mandating officer cooperation during investigations.

(Population: 340,520, number of police: 1100, budget: $400,000.)

Currently, the Pittsburgh Police Union is contesting the CPRBís ability to compel officer cooperation. The matter has not yet been resolved by the court.

3. County of San Diego Citizensí Law Enforcement Review Board (CLERB).

The CLERB was established by voter approval in 1990. The CLERB consists of 11 members appointed by the Board of Supervisors. Members are extensively trained in many areas, including local government structure, laws pertaining to officersí rights, the Sheriffís training programs, operations of the Sheriffís department, and constitutional and civil rights law relating to police misconduct and citizensí rights. The CLERB has a hired staff, including one executive director, two civilian investigators and one administrative secretary. The investigators are required to be experienced in investigation and Californiaís criminal justice system.

The CLERB receives citizen complaints directly. It performs independent investigations which include interviews and examination of the incident scene. The CLERBís rules and regulations give it subpoena power and the right to mandate cooperation from officers. The subpoena power was challenged by the Sheriffís Association but was upheld by the Supreme Court of California. During CLERB investigative interviews, a county sheriff department liaison asks subject officers questions prepared by a CLERB investigator. Board members generate findings from an investigation alone or, if necessary, from CLERB public hearings. The findings as well as disciplinary recommendations are made to the Sheriff, who then makes the final decision on discipline.

The CLERB also reviews and makes recommendations on police policy, investigates and/or reviews investigations of police shootings and deaths in custody, and annually inspects county adult detention facilities. The CLERB handles approximately 200 cases a year.

(Population: 800,000, number of deputies: over 2000, budget: $300,000.)

4. San Francisco Office of Citizen Complaints (OCC).

The OCC was approved by the voters in 1982. The OCC is a fully staffed city agency under the direction of the Police Commission, which is a body of five volunteer citizens appointed by the Mayor. The OCC has a director, 16 staff civilian investigators, four supervisory investigators, one policy/outreach specialist and eight support staff. The OCC staff receive extensive training in police procedures supplemented by a 400-page manual.

The OCC handles over 1000 complaints per year and has the responsibility of investigating all complaints, with some exceptions. Many layers of review exist for the investigations, and private evidentiary hearings are an option at complainant request with director approval. All sustained cases are sent to either a private hearing in which the chief of police presides or, if the cases are of a more serious nature such as excessive force, crowd control or disparate treatment, they are adjudicated in a public Police Commission hearing. Officers can choose to close this hearing to the public but seldom do so.

The OCC is very active in making policy recommendations, many of which have been implemented by the Police Bureau. The OCC is also very active in community outreach and implements the Early Warning System. Staff members participate in some of the police academy training classes and monitor police action during demonstrations. The City Charter and a Police Department General Order mandate officer cooperation during an OCC investigation.

(Population: 745,774, number of police: 2,000, budget: $2 million.)

5. Honolulu Police Commission (HPC).

The HPC consists of seven volunteer civilian commissioners appointed by the Mayor and confirmed by the City Council. Established in 1932, the HPC was authorized in 1972 to hire its own civilian staff, comprised of an executive officer, three civilian investigators, and four support staff members.

The HPC receives complaints directly. Investigations are performed on signed complaints that are judged not to be speculative. The investigators issue a report on each complaint and refer those reports to the Commissioners, who decide cases in executive sessions. The HPC makes findings which may not be overruled by the Chief, who decides disciplinary action on sustained cases. The HPC handles approximately 200 cases annually. It also reviews and makes recommendations on the annual police budget to the Mayor. The HPC does not have subpoena power. Police officers are aware of the Garrity Warning and generally agree to cooperate during HPC investigations. Accused officers who refuse to cooperate automatically receive a sustained finding by HPC.

The HPC reviews policy but does not make policy recommendations. It also holds public hearings to allow citizens to voice concerns regarding police misconduct. The HPC also has the ability to hire and fire the Police Chief.

(Population: 875,000, number of police: 2,000, budget: approximately $450,000.)

6. San Jose Independent Police Auditor (IPA).

The creation of the Office of the Independent Police Auditor (IPA) was approved by the City Council in 1992. The IPA is appointed by the City Council and has a staff of three, including one assistant director and two complaint analysts.

The IPA can receive complaints but must turn them over to Internal Affairs for investigation. The IPA reviews police investigations of all excessive force complaints and no less than 20 percent of all other complaints. The IPA can interview civilian witnesses in reviewing investigations and can attend the Internal Affairs interview of witnesses and police officers. The IPA cannot ask questions during such Internal Affairs interviews, but can suggest questions to the interviewer. The IPA attended 21 out of 118 interviews conducted by Internal Affairs in 1999. If the IPA thinks it necessary, its representative can make a written request to the Police Chief for further investigation. The IPA can perform follow-up investigations after an Internal Affairs investigation is completed. A follow-up investigation allows the IPA to interview witnesses, inspect the scene of the incident, review all police reports and examine all physical evidence. The IPA can only interview the subject officer through a police investigator, who repeats the IPAís questions to the officer. If the IPA reviews a case and disagrees with a finding, the IPAís representative can discuss the case with the Chief and City Manager. The IPA and Internal Affairs do not have subpoena power.

The IPA makes policy recommendations to the police department. Public hearings are not held for the purpose of policy review. In 1999, the IPA audited the 161 cases investigated by the police Internal Affairs department.

(Population: 750,000, number of police: 1,367, budget: approximately $300,000.)

C. Expert Consultations.

1. Professor Sam Walker:

The work group consulted two experts in researching the issue of effective police oversight. The first, Sam Walker, a criminal justice professor at the University of Nebraska at Omaha, favored the audit model, and opined that PIIACís monitoring reports, demonstrated that PIIAC was fairly effective. He found IAD's lack of timeliness, taking as much as two years in some cases, unacceptable. He recommended that the problem be corrected immediately, and that the Police Bureau and Mayor as Police Commissioner respond to PIIAC's recommendations. He also recommended that PIIAC Advisors and staff examiner be trained extensively in areas such as police procedures, similar to board members and staff in other review boards.

Professor Walker suggested that Portland needs to implement a quality control system such as Minneapolis' evaluation forms, which are completed by complainants and officers involved in the citizen complaint process. He recommended that PIIAC monitor the function of the Police Bureau's Early Warning System and that the Police Bureau collect data on traffic stops designed to ferret out racial profiling. Though Professor Walker favored the audit model, he noted that Minneapolis and San Francisco had independent citizen police review boards that were effective. Professor Walker refuted the notion that citizen based review boards are more lenient towards police than internal police review, calling that idea a myth based on outdated and incorrect data. Professor Walker claimed that there is no evidence that civilian investigation is any better than police investigation and in some cases, such as in New York and Philadelphia, it was ineffective. He claimed that a data comparison of review boards would not be determinative of which ones exemplify best practice models because all boards use different criteria. He reminded the work group that the basic goal for police oversight is to help the Police Bureau become more professional and accountable.

2. Mark Gissiner, Past President of IACOLE.

The second expert, Mark Gissiner, served two terms as president of the International Association For Civilian Oversight of Law Enforcement (IACOLE). He worked as a trained civilian investigator for Cincinnati's police oversight system for ten years. He helped set up independent review boards in Minneapolis, San Diego County, Memphis and Orange County, Florida. Mr. Gissiner consented to speak to the work group by phone from his home in Cincinnati at no expense. Mr. Gissiner told the group that he finds the audit model weak and opined that what is missing in such a model is independent investigation. He stated that independent investigation is crucial in achieving impartiality in citizen complaint investigations and in establishing community trust. He stated that civilian investigation has less impact on police officers than they fear, but that as public employees they have to understand that the public has a right to know most everything about their job and conduct. Mr. Gissiner informed us that police investigators typically do not have very much training because experienced officers usually are not assigned for long periods of time at internal affairs divisions. Some civilian investigators are trained by other experienced investigators while attending training courses. Some boards hire ex-police investigators if the availability of trained civilian investigators is limited in their cities.

Mr. Gissiner favors making the citizen complaint process as public as possible, including hearings. He does not favor sworn testimony requirements for complainants and officers, since hearings for citizen complaint cases are of an administrative nature. Mr. Gissiner also claimed that the independent citizen police review boards in Minneapolis and San Francisco were effective boards.

VII. PROPOSED CHANGES TO PIIAC.

A. Introduction.

The work group considered different components of a civilian police oversight system during its deliberations. Straw votes were taken as well as a final vote on recommendations, a record of which is set forth in Appendix A.

While the work groupís recommendations support adding powers to PIIAC such as independent investigatory power, there was no final consensus as to whether the resulting model should be an arm of the City Council, similar to the current PIIAC model, or a fully independent board. City Attorney Jeff Rogers opined that if the review board was structured as a completely independent body and not an arm of the Council, the City Charter would have to be amended.

Even as an arm of the council, a review board would still retain the majority of the powers recommended by this work group. In either case, the Council would continue to select board members, receive reports, and possibly act as an appellate body to the boardís findings.

The following discussion synthesizes the votes and explains the conclusions reached by the work group.

B. Review Board Scope of Authority.

1. Independent Investigations.

(Recommendation #3) That the civilian review system have the ability to perform independent investigations of allegations of police misconduct.

The ability of a police review board to perform independent investigations is a key component in the work groupís recommendations, (vote 12-6-0). This recommendation is based upon the work groupís assessment and research of other boards, consultation with experts (although the work group did note the contrary view by Dr. Walker), the positions of the local NAACP, League of Women Voters, Ecumenical Ministries Organization, the Albina Ministerial Alliance and the opinions offered by citizens at the public forum. At this juncture, in order to establish credibility in the eyes of Portlandís citizens, investigations must be performed by civilian investigators outside the jurisdiction of the PPB. Too many citizens feel intimidated by a police oversight system in which the police investigate other police officers.

Reports from several groups such as Amnesty International and the U.S. Justice Department demonstrate that there are inherent deficiencies in police investigations of alleged police misconduct. 14 Further, as mentioned previously PIIAC monitoring reports showed similar deficiencies in the investigation of citizen complaints but not in internally generated complaints, which suggests a lack of impartiality by the police. 15

Expert Mark Gissiner, having worked in a citizen police review board for ten years, stated during his phone conference with the work group that civilian investigation was crucial for impartial examination of citizen complaints and in achieving community trust and satisfaction. Mr. Gissiner stressed that after experiencing a civilian review board model, Cincinnati citizens would never go back to the old style audit review structure of the past. Police oversight expert Eileen Luna also favors civilian investigation. Ms. Luna is a professor at Arizona University and has over 14 years experience with civilian investigation with citizen police review boards in Berkeley, San Francisco and San Diego County. Ms. Luna worked with Professor Walker in advising Albuquerqueís Task Force on Police Oversight. Ms. Luna states that civilian investigation allows for more effective police oversight and is important in establishing community trust. 16

Concerns were raised by some members that the civilian investigators might not be competent and would not understand police work. However, information gathered from other review boards indicated that those boards were able to hire experienced civilian investigators, some having as much as fifteen years experience in investigation. The investigators were also thoroughly trained in police procedure. The boards that this work group researched provide ongoing training for the investigators to sharpen their investigative skills. San Francisco currently has 41 qualified civilian investigator applicants on file. 17

Like the boards above, a Portland review board could set up an investigative protocol, construct layers of review for investigations, and provide training in police procedures to its investigators. Such procedures are being executed successfully in boards judged effective by police oversight experts Sam Walker and Mark Gissiner. One advantage to a board with its own investigatory power is that it can fire its own civilian investigator for ineptness but does not have the ability to fire a police investigator.

Reports particular to Portland note that officers do not relish being assigned the task of investigating their fellow officers. This type of pressure does not encourage objectivity. For example, as the Portland City Auditor stated:

According to the conversations we held with current and previous staff members and a former supervisor of IID, the Internal Investigations Division is not a desirable assignment in the Bureau. Investigators do not enjoy investigating their peers because it isolates them from their co-workers in a profession already somewhat apart from the general community. 18

This same observation was made ten years earlier in a report issued in 1982 by the Portland City Club. The report states:

According to Chief Still, IID duty is considered a highly undesirable assignment for which officers do not volunteer. .... Investigators may have worked with accused officers previously and may have to work with them subsequently. Both the investigators and the accused officers are members of the same union, and the union challenges most of the sustained complaints. Additionally, officers tend to bind together because their lives may rest in the hands of one another on their next shift." 19

In other words, the task of investigating oneís fellow officers carries with it potential conflicts and undue peer pressure which can erode the objectivity of the position.

Based upon a statement made by an IAD detective, the same City Club report noted that only after six months (of a one year service assignment) were police investigators comfortable with IAD procedures. 20 Typically, an assignment to IAD lasts no more than two years.

During his visit to the work group, Chief Mark Kroeker acknowledged that Internal Affairs is not a desirable assignment for officers. All in all, the objectivity of one officer investigating another is questionable.

Another concern was raised that civilian investigation will violate officers' rights. However research provided to the work group demonstrated that other review boards do not violate officers' rights. In fact, the opposite seems to be true.

For example, San Francisco civilian investigators come in as early as 6:00 A.M. and stay as late as 11:00 P.M. in order to set up interviews that accommodate officersí scheduling. 21 In 1999, close to 90 percent of officers involved in the citizen complaint process in Minneapolis found the review board's investigations were performed in a manner that was impartial, fair and respectful. 22

Members opposing civilian investigation also contended that independent review boards do not work well noting those in New York City and Philadelphia. Also there were claims made that blue ribbon committees around the country uniformly opposed citizen review questioning the modelís work ability and legal viability. Further, there were suggestions made that Minneapolis' CRA is failing because it had only sustained one case in 1999.

These concerns are addressed by appropriate research. According to a New York Civil Liberties Union five year study of New Yorkís review board, until recently the New York citizen review board was underbudgeted and understaffed. The board could only afford to hire civilian investigators with entry level experience thus explaining its inadequacies. 23 Further, according to a recent Human Rights Watch report, the Philadelphia review board is also understaffed. The civilian investigators handle up to 40 cases each at any given time which is nearly three times that of the IAD investigators in the same city. 24 Minneapolis did have a low sustained case rate in 1999. But, according to Professor Sam Walker a "low sustained rate" is not a true measurement of a board's success. Other statistics from Minneapolis indicate that the board is working. For example, Pat Hughes, the boardís director reports that the excessive force cases in Minneapolis dropped by 50% after the creation of the board and many policies regarding police actions were improved as a result of the board handling every case. Many of the cases that would have been sustained were sent to mediation since they were of a less serious nature explaining the low sustained rate. 25

There was also a question raised about whether independent investigations would require changes to the City Charter. The work group posed a number of legal questions regarding police oversight to City Attorney Jeff Rogers, and as to this issue, he responded:

Therefore, both the Council as a whole, and the Mayor individually, have charter authority to empower a review body of city employees or private citizens to investigate allegations of police misconduct and to compel the attendance and testimony of witnesses for purposes of conducting investigations. 26

In sum, the majority of the work group concluded that Portland cannot afford to allow police investigation of citizen complaints to continue especially since the current system inhibits complaints from being filed. The work group urges the Mayor to change PIIAC by giving it the ability to make independent investigations of alleged police misconduct.

2. Optional Police Investigation

(Recommendation # 4) There should not be dual investigation of citizen complaints; however, civilians should have the ability to choose either IAD or the civilian review board to do the investigation, but not both.

The work group discussed the role of IAD after the establishment of a review board and concluded that the IAD should continue to serve both as a vehicle for internal Police Bureau complaints (officer vs. officer) and continue to serve as an optional vehicle for citizen complaints. (For a table of IAD statistics from 1994-1999 see Appendix U). However, the work group concluded that citizens must designate that their complaint be processed either by IAD or the review board, but not both (vote of 11-6-1).

In most cities which have citizen police review boards, the police internal affairs investigators and the civilian investigators do not handle citizen complaints simultaneously. For example, after San Francisco created civilian review, it retained a small number of internal affairs investigators to handle only internally-generated complaints about police misconduct. Review boards in Minneapolis and San Francisco do not run parallel investigations on citizen complaints. Consultant Mark Gissiner reported to the work group that police internal affairs divisions are generally relieved not to have the burden of investigating other police officers once civilian investigation is established.

The work group reasoned that two layers of investigation for each citizen complaint would not serve the best interest of the community, especially since such a system would be too costly. The work group anticipates that the vast majority of citizen complaints will be processed through the review board, thereby allowing a reallocation of budget from the IAD to the review board.

3. Compelling Civilian and Officer Testimony.

(Recommendation #20) The board should be granted power to compel testimony of witnesses, including police officers, subject to constitutional safeguards including the right to counsel, and that the City Council should implement changes to the City Charter or recommend changes to state law as necessary to effect this power.

After extensive discussions and research on the power to compel testimony, the work group concluded that this power is a necessary component of an effective review board, (vote, 12-6-0). By way of background, it should be noted that PIIAC already has the authority to require witnesses (other than the IAD commander) to appear involuntarily before the City Council or the Citizen Advisors, if "extraordinary circumstances" exist. 27

However, a legal opinion issued in 1988 limited PIIAC's subpoena power over police to asking questions about the Internal Affairs process, explaining that PIIACís scope of authority is limited to reviewing IAD investigations.

Because of the legal ramifications involved with this issue, the work group sought and obtained an advisory opinion from City Attorney Jeff Rogers. Appendix G. Jeff Rogers noted that the current Collective Bargaining Agreement with the Portland Police Association "... does not contain any language that specifically prohibits mandatory cooperation with a civilian investigating body." However, Rogers noted that an action by the Council or Mayor to subpoena police officers would constitute a mandatory action subject to the restraints imposed by the collective bargaining agreement. Rogers did not address whether PIIACís current authority to subpoena witnesses could be expanded without conflicting with city code or the collective bargaining agreement.

Article 61 of the contract between the City of Portland and the Portland Police Association provides certain rights for officers prior to being interviewed in an IAD or EEO investigation. These rights include giving officers advance notice, that the interview take place in a PPB or mutually agreed upon facility, limiting the nature and scope of the investigation to the conduct alleged, and that officers be afforded the right to contact and consult privately with an attorney of his or her choosing or a representative of the Union. (Appendix H contains excerpts from the current contract between the City of Portland and the Portland Police Association, including Article 61, the Portland Police Officersí Bill of Rights Preamble.). None of these contractual rights have inherent conflicts with a carefully crafted civilian review board model designed to protect these officer rights.

Many of the citizen police review boards, such as Minneapolis and San Francisco, secure officer cooperation by using the Garrity Warning, which protects an officer from incriminating his/her self in future proceedings while providing that an officer must cooperate fully with investigations regarding his or her conduct as a public employee or be subjected to dismissal. 28

In its deliberations, the work group considered how this issue is handled by other boards. See Table below. A more detailed chart is attached at Appendix I.

|

Citizen Police Review Board |

Garrity Warning Issued |

Police General Order |

City Ordinance Language |

Subpoena Power |

|

Minneapolis (CRA) |

yes |

no |

yes |

no |

|

San Francisco (OCC) |

yes |

yes |

yes |

yes |

|

Honolulu (HPC) |

no |

no |

yes* |

no |

|

San Diego County (CLERB) |

no** |

no |

yes*** |

yes |

|

Pittsburgh (CPRB) |

yes |

no |

yes |

yes |

*If an accused officer refuses to cooperate, HPC automatically sustains the complaint he/she is involved in.

**A sheriff department liaison issues the Lybarger Warning, based on a California case and similar to the Garrity Warning.

***Section 6 of the CLERBís Regulations mandates officer cooperation; however, the CLERB and the Sheriffís Association agreed to the following procedure: During CLERB interviews, a Sheriff Department liaison presents questions prepared by CLERB investigators to the accused officer.

The administrative rules for the Minneapolis CRA mandate officer cooperation during citizen complaint investigations. Before an officer is scheduled for an interview with the CRA, the Chief of Police is asked by the CRA to issue the Garrity Warning to the officer. 29 In San Francisco, a police department general order and the City Charter mandate officer cooperation with the OCC's citizen complaint investigations.

Many review boards with the power to compel testimony were legally challenged by their cities' police unions. The courts upheld the boards' authority in nearly every case. 30

City Attorney Rogers suggested that a board could only compel officer testimony if it had "disciplinary authority." Rogers supported this opinion by relying upon a case decided by the Colorado Court of Appeals, City and County of Denver v. Powell. 31 In this case, the court held that the Denver review board (PSRC) could not compel officer testimony because the PSRC only had the power to make policy recommendations and not disciplinary recommendations. In other words, the board was not an "integral part of the discipline process." Id.

In its decision the court cited a New York case, Pirozzi v. New York in defining what it meant by the term "integral part of the discipline process." The court explained that:

the PSRC's lack of involvement in disciplinary proceedings distinguishes this situation from Pirozzi because there the New York police citizen review board is an integral part of the discipline process and officers are compelled by specific police department regulations to give a statement to that review board under threat of termination.

City and County of Denver v. Powell, 969 P.2d 776 (1998).

The New York Citizen Review Board cited in Powell is limited to recommending discipline to the New York police chief on sustained cases. The police chief is not required to follow such recommendations. 32

In other words in order for a review board to have "disciplinary authority", as Jeff Rogers terms it or as the court states "an integral part of the discipline process" that board must have the power to make disciplinary recommendations coupled with the threat of employee termination if the officer does not cooperate with the process. In recommendation #16a, the work group voted to give the review board the power to make disciplinary recommendations to the Chief. The work group concludes that it appears that formation of a review board will not meet insurmountable legal challenges. 33

In the final analysis, the work group concludes that the ability to compel officer testimony, in addition to subpoena power of other witnesses is essential for an effective police oversight system. The work group trusts that officers would welcome the opportunity to tell their side of the story in the neutral, professional setting provided by civilian review. However, for those officers who may be unwilling to cooperate with civilian investigation the ability to compel testimony is a critical component of the process. In view of the practices of the other boards, the work group expects that the review board will develop internal rules which would defer or delay exercising the power to compel witness testimony until underlying criminal, grand jury or civil litigation is completed. The work group does not intend that the review board fact finding process will interfere with ongoing civil or criminal litigation. Indeed, if a citizen has chosen civil litigation as his or her preferred strategy then the review board should defer to the complainantsí choice.

4. Binding Authority on Finding of Misconduct.

(Recommendation #13) (a) That PIIAC (if it remains an Auditing Body) be able to change a Police Bureau finding and that this disposition be binding; (b) that the citizen review board have the authority to make a final finding that is binding.

One of the criticisms heard frequently of the current PIIAC is that the Police Chief can ignore PIIACís recommendation to change a Police Bureau finding as to whether misconduct occurred. Therefore, the work group recommends that an independent review board be given the power to make a final binding disposition about a complaint based on the evidence presented to it by independent investigators. The work group also recommends that if PIIAC is retained as an auditing body, it be able to change an IAD finding and make its disposition binding (vote 11-7-0).

The current PIIAC is empowered by the City Code to determine if the IAD investigation is not supported by the investigation findings ". . . and what determinations should have been made if the Advisors conclude that no additional information is warranted." . 34

In 1996, PIIACís Advisors voted to propose changing a finding in an appealed case to "sustained." The City Council voted 4-1 to send that finding to the Chief, and in that case, the Chief agreed. However, in 1997, two other cases were also sent back for changed findings. In these cases (#96-22 and #96-18), the City Council voted 3-2 and 4-1 to find the allegations were "sustained." In those two cases, the Police Chief refused to change the findings. Sensing a problem with the PIIAC structure, the City Council called an "informal" session in February 1998, at which the Chief stated that he would not come before the Council to explain why he in effect "overruled" the actions of the Council.

Several Council members and a large number of Portland citizens were concerned that the current structure allowed the appointed Police Chief to ignore a majority vote of the elected City Council. One former PIIAC Advisor, Emily Simon, resigned after these cases. Professor Sam Walker, who favors the audit model, nevertheless stated in a letter to Mayor Katz: "If PIIAC is to retain its effectiveness and credibility with the public, it is imperative that its recommendations be acted on." 35

The vast majority of citizens who attended the work groupís public session expressed the opinion that the review boardís fact-finding decision be binding. This was also a key component of PAC-2000's initiative, and is one of the four points proposed by the NAACP. 36 Other jurisdictions in which review boards have final authority on the disposition of civilian complaints against police include Minneapolis and San Diego County.

The founding fathers showed the wisdom to put a civilian in charge of the nationís military. Similarly, at the local level, the work group concluded that civilians, either through the Council or a review board should have the final say as to the merits of a complaint against a police officer.

5. Recommendation to Impose Discipline.

(Recommendation #15) That the final say on discipline belongs to the Chief of Police.

(Recommendation #16a) That the citizen review board have the ability to recommend that discipline happens, and that the Chief/Commissioner should respond in writing within thirty days with an explanation if the recommendation is not accepted.

The work group unanimously recommended that the final determination for the type of discipline imposed (if any) belongs to the Chief of Police. This proposal is not intended to remove the statutory powers of the City Council as an officer's employer to make such a decision.

The work group recommends that the review board have the ability to recommend whether discipline should be imposed (Vote 12-6-0). The Chief and his/her superior, the Commissioner of Police, would not be required to impose discipline, but would be required to explain in writing if the review boardís recommendation is not accepted. This is consistent with the current provision in the PIIAC ordinance, requiring the Chief to respond to PIIACís recommendations.

The work group determined that a recommendation to impose discipline was critical to establishing the credibility of the review board. Those opposed to this motion felt that even the recommendation of discipline would "usurp" the power of the police chief. Members in favor noted that simple recommendations which would not be binding would not take power away from the Chief.

Most important, is that the power to make recommendations regarding discipline would make the review board "an integral part of the discipline process" as defined by the Colorado Court of Appeals, allowing the board to legally exercise its additional recommended power to compel testimony.

At the same time, the work group was clear that the review board should not be given the authority to determine what type of discipline should be imposed (voted down 6-10-2). It should be noted that the review boards in Pittsburgh, San Francisco and San Diego County have the power to recommend the type of discipline imposed.

In sum, the work group recommends that the review board be given the power to recommend to the Chief that discipline be imposed in a case where a sustained finding has been made.

6. Public Hearings and Policy Recommendations.

(Recommendation #18) That regardless of the model chosen, hearings will be public with the exception of personnel, medical, employment, and criminal issues and at the discretion of the committee.

(Recommendation #19.) That the model will allow for public hearings to discuss police policy and recommend changes to the police chief/commissioner.

(Recommendation #5) The Police Chief and the Police Commissioner should be required to respond in writing to policy recommendations within sixty days; and that if the review board is not satisfied with the Chief's written response, he must publicly present his response to the City Council.